Maximising welfare benefits by contextualising case management

This is article twenty-two in an RCVS Knowledge series of features on patient safety, clinical human factors, and the principles and associated themes of Quality Improvement (QI).

Scenario

Julie, a friend from home on the local farm, phones you on a weekend. They have an active 7-year-old dog (Daisy) who has had a swelling on one of her front paws (P3). Julie’s vets have been brilliant. Following initial assessment, Daisy was given antibiotics as the raised red area was most likely caused by an infection. The swelling settled initially, but returned a few days after finishing the treatment course. Highly suspicious of a foreign body, it was decided to bring Daisy into the practice to open the area up and flush it out. Julie has called you 6 weeks after this began, as the next logical step offered has been an MRI and potentially another flush out at a referral centre about an hour away. Julie has been quoted £4000, and wants to chat this through with you.

Challenging situations don’t happen only with in-depth or complicated medical or surgical issues; they happen every day and can be tough to navigate. Unresolving wounds or potential grass seed foreign bodies are regular challenges, particularly in the summer months. In charity settings like Dogs Trust, there may be organisational guidance to navigate within the decision pathway with standard protocols. Factors beyond the facts in front of you may be important to consider, for example, whether the owner is able to bathe the patient or care for a wound, or if the animal has challenging living arrangements.

The most common challenge to resources is often financial, however other factors will also have an impact on a wound’s ability to heal; an elderly person, or a person who is living in a homeless setting, may not always be able to keep a bandage dry or wash a wound regularly, so our care plan must factor that in. As vets, we have an ability to deal with diverse cases thanks to the advances in science, however, we also need to balance this with an understanding of the additional patient and care givers/owners’ factors surrounding a case. Bringing care givers/owners into the decision-making process around treatment can help ensure the outcome for the animal is the best one for them in their circumstances.

This may be something we think about more formally. For instance where time is taken to describe how to manage diabetic injections to provide owners with the insight to decide if they can manage this treatment and feel able to cope1 or more informally in appreciating our clients’ circumstances sensitively.

An update on Daisy

In speaking with Julie, you are able to reassure them that the treatment course has been logical and that it seems that their vets are offering them the next step, however there may be other options available including revisiting previous approaches. Knowing yourself that this option may be considered a gold-standard approach, you suggest that Julie speaks with the vet again and explains that they are unsure that going forwards with this is an option and what else might be feasible? You ask Julie to stay in touch with you to let you know the outcome.

Contextualised care

Within general practice, different approaches may be taken based on the balance of feasible options. More recently, contextualised care refers to an approach to cases within the context of their surroundings2 which includes input by the care-giver/owner. The partnership between the client and the vet is focused on maximising the welfare of the patient.

Here at Dogs Trust, we have regular discussions about context where our vet team provides support and guidance to caregivers and vets who may be treating dogs that the charity financially supports. These conversations are always based on maximising their welfare within the setting that they are in. Some examples where context can affect our decisions may include the following:

- Epileptic dogs in a kennel setting. Kennels are busy and although routine is encouraged, with a great deal going on, this can lead to unpredictability. There isn’t always someone to monitor and watch a dog who may have a seizure, and their stability may be compromised in a kennel setting, affecting their welfare.

- A dog living in a homeless setting requiring surgery that will involve complex aftercare. The aftercare will be difficult to manage, and we may be unable to perform the surgery as its success would be affected by the resource available.

- Street dogs, or dogs that we see for only a small proportion of their lives, where we cannot influence or support their care outside this snapshot of time.

All these are examples of circumstances beyond finances that may affect the outcome of a regular treatment plan; considering the context helps maximise welfare benefit and to address patient needs. We often also have protocols or approaches3 to care which can help. In the past this was sometimes referred to as pragmatic medicine, but in more recent times we are concerned with ‘contextualising’ the options available. But contextualised care is relevant to private practice as well – perhaps you can think of situations you have encountered where the circumstances of the client have influenced clinical decision making?

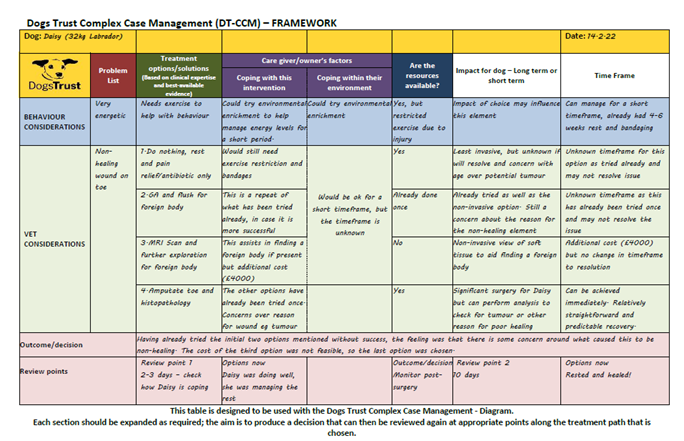

There are many people involved in the care of animals at Dogs Trust. We must consider veterinary surgeons and veterinary nurses, managers and behaviour roles, carers and volunteers who help walk and care for the patients on a daily basis. For more complex cases, specific staff might meet to review and discuss what to do. In order to consider all opinions in the context of an individual animal, Dogs Trust have created a complex case management tool (figure 1, below) which could be adapted as a framework in other settings.4 The tool documents and makes the process clear. It can also outline review points and enable a change in direction to be taken if needed. In addition, the framework offers a way to clearly communicate the decision to others.

Figure 1 Dogs Trust Complex Case Management Framework for Daisy

Download the Dogs Trust Complex Case Management Framework for Daisy

Providing a constructive approach to any decisions made with a caregiver (either an owner or someone in a charity setting) can help open the conversation and address assumptions or unsaid concerns. It can also be valuable when dealing with an owner when specific circumstances involve financial restrictions. Bringing context into care decisions helps to provide the best option to manage individual welfare, because it considers what will be successful in the individual setting, addressing any unsaid feelings.

Sometimes the decision taken can seem extreme - for example, in the case of a dog presenting with a small wound on their toe, you may not initially include amputation of the toe within your treatment options, however infections such as mycobacterium or tumours that may mimic a foreign body infection may raise this up your list. Logical clinical problem-solving helps to understand this better and a framework for complex decisions can be valuable to help achieve such an outcome.

Back to Daisy

Julie phones you back after Daisy’s appointment. Their vet decided, based on weighing up the options alongside Julie, that the concerns over the non-healing nature was heightened now that two approaches had been tried. The MRI may provide a non-invasive view of the issue and potentially more detail regarding a foreign body, however if this didn’t provide more insight it was likely that toe amputation would be a practical choice. The decision table helped to remove any guilt from Julie’s behalf around the funding for an MRI and provided the ability to choose together the best option for Daisy.

Checklist: what you can do next

- Contextualised care is a partnership between care-givers/owners and the veterinary surgeon, all working together for the best quality of life for the patient. It forms part of evidence-based veterinary medicine, which combines clinical expertise with the most relevant and best available scientific evidence, patient circumstances, and care-giver/owner factors – including their ability to care for the patient, their financial circumstances, and their wishes. To find out more and how you can incorporate evidence-based veterinary medicine into your daily practice, access 4 hours of free CPD with the EBVM for Practitioners course.

- Guidelines are a Quality Improvement (QI) tool designed to assist with decision-making in the management of a case based on an appraisal of the current best evidence along with clinical expertise and patient circumstances. Learn how to develop guidelines that benefit your teams and best fit your practice needs by accessing the new QI Boxset Series 4: Guidelines, providing over 7 hours of free CPD.

- Have a look at this award-winning case example to see how the Blue Cross developed guidelines within practice, to deliver a consistent approach to diagnosis and treatment throughout the charity for more than 60 common syndromes and conditions.

- Read about how communication can be improved in this previous QI Feature on Team communication – a core non-technical skill to understand the value of clear and concise language to establish a shared understanding. Communication is a vitally important transferrable skill to help us advocate for the animals in our care whilst considering the patients circumstances and the needs and values of their care-givers and owners.

- Subscribe to inFOCUS to be kept up to date with the latest research papers, critically appraised topics, and more, that have the potential to positively impact patient care. inFOCUS is RCVS Knowledge's editorially independent veterinary journal watch where articles are assessed by the Clinical Review Team who score them for relevance, quality, and interest to the veterinary practitioner. The top-scoring articles are summarised with helpful commentary to assist those based in practice to help improve the quality of care delivered.

References

1. Belshaw, Z. (2019) What is your client thinking and why should you care? Veterinary Record, 181 (19), pp. 517. https://doi.org/10.1136/vr.j5234

2. Skipper, A. et al. (2021) ‘Gold standard care’ is an unhelpful term. Veterinary Record, 189 (8), pp. 331. https://doi.org/10.1002/vetr.1113

3. Dean, R., Roberts, M. and Stavisky, J. (eds) (2019) BSAVA manual of canine and feline shelter medicine: Principles of health and welfare in a multi-animal environment. Quedgeley, Glos: BSAVA.

4. Hanaghan, R. (2019) A case management framework for complex case decisions in a shelter setting. In: BSAVA congress proceedings 2019. Birmingham, 4-7 April. Quedgeley, Glos: BSAVA, pp. 546-547.

About the author

Runa Hanaghan BVSc PgDip SSRM MRCVS

Runa is a Quality Improvement Advisor for RCVS Knowledge and a member of the Quality Improvement Advisory Board. Runa qualified from Bristol University and has had a variety of experience in general practice, working across the UK and returning to her home country of Ireland where she established a sole-charge small animal clinic in Co. Mayo. This community focused clinic presented opportunities to become involved with teaching vet and nursing students along with her excellent veterinary nursing team, leading to a growing interest in checklists and patient safety.

Runa is a Quality Improvement Advisor for RCVS Knowledge and a member of the Quality Improvement Advisory Board. Runa qualified from Bristol University and has had a variety of experience in general practice, working across the UK and returning to her home country of Ireland where she established a sole-charge small animal clinic in Co. Mayo. This community focused clinic presented opportunities to become involved with teaching vet and nursing students along with her excellent veterinary nursing team, leading to a growing interest in checklists and patient safety.

An opportunity to bring this experience and interest to a wider group was taken in 2010 with her appointment as Clinical Lead at Bristol University, teaching undergraduate vet students at their on-site small animal practice. Her role in this busy environment, with ever-changing personnel as students moved through their placements helped to further Runa’s interest in communication and patient safety.

Runa joined Dogs Trust in late 2011 as Deputy Veterinary Director. This is a hugely varied role and one which stays closely connected to the vet practices working alongside the charity nationwide; as well as the procedures that are managed on site at Dogs Trusts rehoming centres. She also sits as a committee member on the Association of Charity Vets with a strong interest in shelter medicine and shelter metrics.

A post graduate qualification in Social Sciences Research Methods allowed her to explore the role of non-clinical skills with undergraduate teaching in a research project. An active interest in patient safety has developed with a deeper understanding of the areas that make up quality improvement. She is not only passionate about where this influences animal welfare through clinical care, but also the wellbeing of the team delivering it. Within the charity, active internal reporting of near miss clinical incidents has been established since 2017, signposting to the wider profession the tools that are now available to them. Significant event audits have also become routine from a veterinary perspective and have broadened within the charity to include other teams who manage and care for dogs at Dogs Trust, enhancing psychological safety and helping to develop a cultural change with a learning culture.

September 2022