Human factors for safer care and a better cup of tea

This is article ten in an RCVS Knowledge series of features on patient safety, clinical human factors, and the principles and associated themes of Quality Improvement (QI).

In Quality Improvement, we talk a lot about improving systems of care. But what does that mean exactly and how do we start? To understand what a system means, let’s look at a familiar system…making a cup of tea.

First, we need a working kettle, water and a method of heating it, a cup and a teabag. We also need a person who knows how to go about making a cup of tea. These are the most fundamental items for making tea. A simple system, right? But what about when people have different tastes? Some want milk. Does it go in before the tea or last, and how much? Some like it sweet – how much sugar, or sweetener, do we add? There are different strengths and brands. In some cultures, drinking tea deserves a ceremony. We can expand even further when we consider how the tea, milk and sugar arrive on our market shelves.

By using tea as a system example, we can begin to see that what is on the face of it, a simple thing to do, can be very complex, especially as we add more people interacting with the system. Just think about how complicated it can be to make a cup of tea for everyone in the practice!

A system is defined as a set of interconnected components that are organized for a purpose. There are interactions between a person (or people), the components and between other systems. The person contributes to the capabilities and limitations of the system as a whole1.

Other systems that will be familiar to us include making a telephone call, obtaining laboratory results, completing a surgical procedure or running a vet practice. All things that require knowledge of the task and people interacting with the parts of the system.

When we first look to improve a system, we must first understand how it works. This is where human factors can help us.

Human factors is the study of all the things that affect our behaviour and performance. You might think, ‘Wow, that’s a lot of things!’ and you would be right. But we can begin by breaking these down into two areas, systems and people.

The systems factors influencing practice

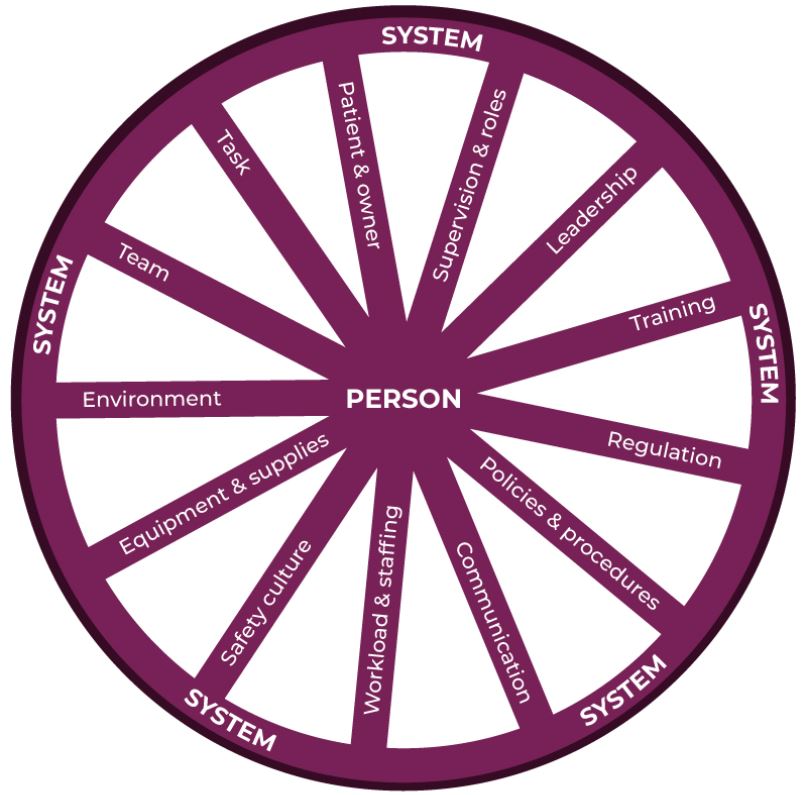

The human factors wheel (Figure 1) represents many of the factors that can contribute to a system’s performance. There may be other factors that are not included in the wheel that you identify that are a part of a system; the aim is to realise that they exist and start asking the question, ‘how is the system affected?’ Multiple factors will be at play, but not all may be activated at once, and we must study how they interact and affect each other.

Figure 1: Human factors wheel, adapted from the London Protocol and RCVS Knowledge Contributory Factors Checklist2,3

When improving systems, context is everything. In the context of tea, the kettle might be broken, you are out of milk or sugar or you don’t have a system for remembering how everyone likes their tea so you sometimes get it wrong. In a clinical context:

- Patient factors might include that the animal had unusual physiology or was not able to be examined due to its aggressive nature.

- Equipment factors may include poor design or a lack of appropriate equipment to manage the patient.

- Team factors could include conflicting team goals or a lack of mutual respect between colleagues.

- Physical environment may include a lack of a staff break room to have lunch or a lack of appropriate kennel facilities to house predator and prey species separately.

- Local protocols might include the lack of a system for gaining informed consent for Cascade use of medicines.

People are at the heart of veterinary practice and therefore are a fundamental part of systems analysis. As a profession, we are well versed in responding to complex and changing environments and the varying needs of our patients and clients. Our human response to these conditions is why things go right so often, but can also be why things go wrong. The breadth and depth of human capabilities and limitations make up the next category – the person.

Individual factors affecting practice

Going back to our human factors wheel (fig. 1) we see that the person is at the hub. How we are as a person and how we are affected by events, influences the entire system. This includes our knowledge and skill level or if we are hungry, tired or injured. We must also think about how developed we are as a person, as this affects our relationships with our colleagues and clients. Highlighting the person in our human factors wheel, in Figure 2, we can start to see a few examples of the factors that affect us at work3.

Figure 2: The Person, a word cloud representation of examples of the individual factors affecting a person at work. Self-development is at the core3.

Using our tea example: Am I aware that someone may need a cuppa? Do I know how to make a ‘good cup of tea’? Am I able to receive the feedback needed to improve? Am I grateful when someone makes a cup of tea for me? In a clinical context examples include:

- Professional knowledge – are there gaps in our clinical knowledge or experience?

- Is our physical or mental health affecting our ability to give compassionate and quality care?

- A lack of experience may contribute to cognitive overload and increased stress, making us more prone to mistakes.

- Good relationships with our colleagues, friends and clients can act as a foundation of support. Without this, work can feel sterile and devoid of any deeper meaning4. When a person experiences incivility from a colleague, patient care and individual wellbeing can suffer5.

- Non-technical skills. These are the cognitive and social skills that underpin our clinical expertise and technical abilities, which are required for safe practice. They include teamwork and communication, situational awareness, leadership and decision-making8.

How do we incorporate human factors into our work?

Human factors principles are most often used in Significant Event Audit (SEA) to identify learning and corrective actions, by using the framework to look at all of the factors that contributed in the context to the lead up to the event. When we start to analyse these events with a human factors lens, we may start to see trends in the data which can focus efforts. We can then go about designing systems that are resilient to these unanticipated events by modifying the design of the system to better aid people10.

We can also use the framework to improve systems of care before an adverse event occurs. Here the shift changes to understanding how things usually go right, since that is the basis for explaining how things occasionally go wrong. The focus is on learning from how people adapt to complex situations and match the conditions needed for work, as this is the reason why human performance practically always goes right6.

Applying this to support the outcome of better tea, a system improvement would be to develop a practice tea chart (Figure 3). Team members record how they like their tea on the chart along with the appropriate letter, so we don’t have to rely on our memory.

Figure 3 – Tea strength colour chart, a system to improve efficiency and happiness in tea.

A new way of thinking about how we work

Human factors enhance our performance through an understanding of how the systems that we work in affect our behaviour, abilities and application of knowledge. It focuses on the human component of the system and how to support both an individual’s capabilities and limitations. These principles help us to better appreciate what we need to be successful in our work, which in turn supports patient welfare and our own wellbeing7.

To navigate the complexities of the human factors wheel, the spokes of the system have to be constantly evaluated. At the hub of the wheel lies individual responsibilities to constantly nurture self-growth and provide feedback on the system3.

Systems are designed to get the results that they get and a bad system can set up good people to fail11. The study of human factors enhances our ability to discover how parts of a system and people work together to produce a result. By looking at our systems through a human factors lens, we are able to better understand our topic of interest, break it down into its component parts and have a better chance at success, including better cups of tea.

Exercise

Identify areas in everyday life where systems have been designed to make it easier to do the right thing or a lack of good design makes it more difficult. An example of good design includes ATM machines that have evolved to not produce money until you retrieve your card. A common area that lacks good design are doors, a handle would indicate to pull and a lack of handle to push, but this is not always intuitive and we do not often stop to read signs. In those areas with bad design, how would you improve it?

Checklist: What can you do next?

- Learn about Significant Event Audit with our free CPD course.

- Use a contributory factors checklist to help identify the root cause of an event.

- Read our Significant Event Audit case examples to see how other practices have improved systems.

- Listen to Richard Killen, former Director of Clinical Services at CVS and Angela Rayner, Clinical Services Manager at CVS and current RCVS Knowledge Quality Improvement Advisor, discuss how to embed ‘systems thinking’ into a practice team.

- Listen to Suzette Woodward, a paediatric intensive care nurse who is now a Professor in patient safety, discuss the latest safety concepts and science that are sweeping the NHS - as well as what we could do differently.

- Listen through the steps of a Significant Event Audit, as Alice Bird talks through a post-operative complication that occurred in equine practice, including how a blame culture was avoided, what lessons were learned, and the resultant processes that were put in place.

References

1. Narkevicius J. (2008) Human Factors and Systems Engineering – Integrating for Successful Systems Development. Proceedings of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society Annual Meeting. 52 (24), pp. 1961-1963. doi:10.1177/154193120805202409

2. Taylor-Adams S. and Vincent C. (2004) Systems analysis of clinical incidents: the London protocol. Clinical Risk, 10 (6), pp. 211-220. doi:10.1258/1356262042368255

3. Rayner A. and Caine A. (2021) The role of personal development in human factors (interview).

4. Carlson K. (2019) The importance of relationships to healthcare delivery [Multi Briefs: Exclusive] [online] Available from: http://exclusive.multibriefs.com/content/the-importance-of-relationships-to-healthcare-delivery/medical-allied-healthcare [Accessed 17 June 2021].

5. Incivility: The facts [Civility Saves Lives] [online] Available from: https://www.civilitysaveslives.com/infographics?lightbox=dataItem-j9wmt66l [Accessed 17 June 2021]

6. Hollnagel E., Wears R.L. and Braithwaite J. (2015) From Safety-I to Safety-II: A White Paper. The Resilient Health Care Net. Published simultaneously by the University of Southern Denmark, University of Florida, USA, and Macquarie University, Australia.

7. NHS England. (2013) Human Factors in Healthcare [online] Available from: https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2013/11/nqb-hum-fact-concord.pdf [Accessed 18 June 2021]

8. The Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh. (2021) Non-Technical Skills for Surgeons handbook. Available from: https://www.rcsed.ac.uk/media/ypmnkyhn/notss-handbook.pdf [Accessed 22 June 2021]

9. Zohar, D. Spiritual intelligence: A new paradigm for collaborative action [The Systems Thinker] [online] Available from: https://thesystemsthinker.com/spiritual-intelligence-a-new-paradigm-for-collaborative-action/ [Accessed 22 June 2021].

10. Russ A.L. et al (2013) The science of human factors: separating fact from fiction. BMJ Quality & Safety, 22 (10) pp 802-808. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2012-001450

11. Deming, W.E. (1993) A bad system will beat a good person every time [Deming Institute] [online] Available from: https://deming.org/a-bad-system-will-beat-a-good-person-every-time/ [Accessed 28 June 2021]

About the author

Angela Rayner BVM&S PgDipPSHCF MRCVS

Angela is a Quality Improvement Advisor for RCVS Knowledge, Director of Quality Improvement for CVS, and is an RCVS Knowledge Champion for her role in improving CVS’ systems for controlled drugs auditing.

In 2021, Angela completed a MSc in Patient Safety and Clinical Human Factors at the University of Edinburgh. The programme supports healthcare professionals in using evidence-based tools and techniques to improve the reliability and safety of healthcare systems.

It includes how good teamwork influences patient outcomes, key concepts around learning from adverse events and teaching safety, understanding the speciality of clinical human factors, as well as the concept of implementing, observing and measuring change, monitoring for safety, and it focusses on quality improvement research and methodologies.

July 2021