Learning from everything: Safety I and Safety II

This is article twenty-seven in an RCVS Knowledge series of features on patient safety, clinical human factors, and the principles and associated themes of Quality Improvement (QI).

On the first Thursday of every month the team at Admiral Vets gather to discuss challenging cases for an hour after work. They enjoy the opportunity to learn new tips on how to treat their more complicated surgical patients and solve medical conundrums whilst munching on pizza provided by the practice. This month the agenda stated:

1. Felix, diabetic cat

2. Lucky, tail wound

3. Thank-you cards,

As the team recalled the listed patients they wondered if the third item was a typo, meant for another list…

A universal feature of high performing teams is the importance they place on improving and learning. Accepting that even the best teams have room to grow, high performing teams value feedback and seek to understand and learn from adverse or unexpected events. They look for opportunities to grow by nurturing a culture of continual learning and improvement, and therefore they are more effective and innovative.

Whether you are listening to football managers, business directors or healthcare professionals, the same theme frequently emerges; to improve we must first observe, listen with fascination and seek to understand. By doing this we can learn, and then consider change.

Within the veterinary profession, learning often becomes synonymous with Continuing Professional Development (CPD) – leaving the practice to learn something new – a new clinical technique or ways to expand and improve clinical knowledge. However, CPD is any type of activity relevant to what you do that you learn from. It is just as important to learn from everyday work and to carefully consider the challenges you face: what went well, what could have gone better and what could be done differently next time.

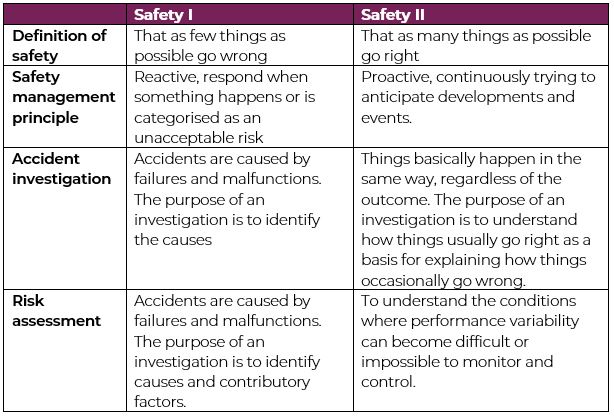

Historically the starting point of safety concerns in healthcare settings has been the occurrence of accidents or adverse outcomes and to seek to remove or eliminate them to ensure that as few things as possible go wrong. This is known as Safety I (said as safety one). Using Safety I, we manage safety by reacting or responding when something happens. The purpose of accident investigation in Safety I is to identify causes and contributory factors of the adverse outcome through Significant Event Auditing, and work towards eliminating causes or improving barriers to future occurrence.

An opportunity to learn from an adverse outcome: Felix

Felix was a diabetic cat who had been a frequent visitor to the practice after his diagnosis a year ago. His family were dedicated to his care and he had been doing well till today when he came in collapsed and unresponsive. He had deteriorated suddenly and the difficult decision to put him to sleep was made. The family and the team at Admiral Vets were devastated. After a busy day, the first half hour of this evening’s meeting was dedicated to a debrief about Felix, what went well with his care, what were the opportunities to improve, and what needed to be done now.

However, this is only a small part of the picture as illustrated by Erik Hollnagel in his white paper from Safety I to Safety II1 . If the statistical probability of a failure is 1 out of 10,000 we can expect things to go right 9, 999 times out of 10,000. Whilst we do not know the failure rate in veterinary healthcare, it is safe to assume that things go right much more frequently than they go wrong. Therefore, if we only focus on the things that go wrong, we are missing a huge opportunity to learn.

Appreciating that both error and excellence occur in equal measure, Hollnagel suggests we look at safety differently - which is called Safety II (said as safety two).

Table 1: Adaptation of Hollnagel et al.'s Overview of Safety-I and Safety-II.

Managing safety through the lens of Safety II, we proactively and continuously try to anticipate developments and events, and we seek to understand how things usually go right as a basis for explaining how things occasionally go wrong.

An opportunity to learn from success: Lucky

Lucky was admitted several weeks ago with a nasty wound on his tail after being attacked by another dog in the park. Nadia, the vet who treated Lucky, had today seen him for his last recheck and was so pleased with his progress she wanted to share the wound protocol she had recently learned at a CPD event which had worked so well for Lucky.

“Success has a much greater influence on the brain than failure.” Earl Miller

Receiving feedback and learning from success forms longer lasting memories which are more rapidly formed. Psychological and learning literature finds that positive feedback improves self-efficiency, improves motor learning and retention of skills, improves memory formation, improves intrinsic motivation, improves wellbeing, improves relationships, and offers moral reinforcement. All better than negative feedback. Therefore, it makes tremendous sense to recognize success and learn from excellence 2,3,4,5,6.

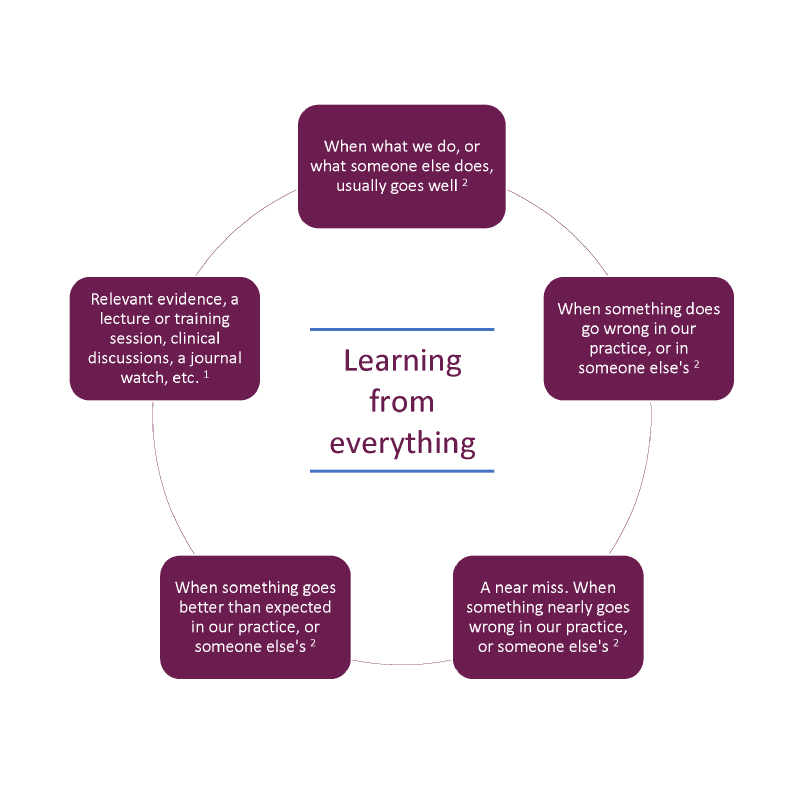

In this article we are not positioning learning from error and learning from excellence as an either/or, but we are highlighting the importance of both.

For example, in order to reduce the cardiac arrest rate by 50% across NHS Lothian, an extensive and comprehensive review of cardiac arrests and medical emergency calls was carried out, data was gathered from everywhere to achieve a greater understanding of what both failure and success looked like. By learning from all aspects of the spectrum it was possible to design interventions to enable cardiac arrests to be greatly reduced.

1 Critical appraisal tools can help you appraise the evidence for validity. This can be applied across all evidence presented to you.

2 Significant event audit, debriefs, and root cause analysis can help you learn from everyday practice. Significant event audits can be used to learn reactively from when things go well (take note of thank you letters), or not so well and where there is a near miss (for example, complaints and event reports). The Contributory Factors Checklist can be used as part of Significant Event Auditing, and can also be used to help teams better understand the components that lead to good running of everyday practice (Safety II).

Remember that you can learn from what happens in your practice, but you can also learn from what happens in other practices and even other industries.

Figure: Learning from everything, by RCVS Knowledge (2023).

In a paper published by Gillespie and Reader in 2020 (8), the analysis of the content and aims of 1,267 patient letters of compliment (across 54 English hospitals) was discussed. These letters were found to acknowledge extra role behaviours such as acts of compassion or team members going the extra mile to run additional tests or offer support. They also identified and attempted to encourage a patient-centric vision for high-quality healthcare. They acknowledged exceptional practice and caring relationships. It found that patient gratitude, when fed back to the team, increased motivation and reduced burnout. Social recognition bolstered motivation and improved resilience of the healthcare system.

Learning from gratitude: Thank you letters.

Having read the paper by Gillespie and Reader, Karen, a veterinary nurse, collected the last 10 thank you letters that the practice received, and gathered the themes and sentiments of gratitude shared by the authors to share with the team. They learned that regular updates were often mentioned in the letters, and discussed how they could ensure that these were incorporated into everyday communication with clients.

“What are your thank you letters telling you?”

As previously mentioned, in this article we are not positioning learning from error and learning from excellence as an either/or but highlighting the importance of both and how they work in synergy to ensure that we learn from everything and appreciate the whole picture, because we know that when we are learning continuously, from everything, we can we ensure high performance in teams and through high performance we can make sure that patient safety is at its peak.

As the team dispersed after the learning discussion, the chairs tidied and pizza boxes recycled, the chatter in the team turned to how much they had all enjoyed hearing about Lucky's wound protocol, how wonderful it was to hear all the positive and grateful comments from the thank you cards, and how sharing their thoughts about Felix helped them all feel just a little bit better. The team at Admiral Vets each went home feeling positive and thankful that they worked with such a wonderful team.

Checklist: What can you do next?

- Dispel myths about what counts as CPD and what can be logged on 1CPD. Find out more here.

- What is hot and cold debrief, how does it help with patient safety and supporting team members after a difficult or distressing case? Read our previous feature article.

- Significant event audit, debriefs, and root cause analysis can help you learn from everyday practice. The Contributory Factors Checklist can be used as part of significant event auditing to identify the factors that led to the event, and can also be used to help teams better understand the components that lead to the running of good everyday practice.

- “The power of a growth mindset” by Professor of Learning, Bill Lucas, was an RCVS Knowledge recorded session at the SPVS-VMG Focus on Leadership and Management Virtual Summit. Here Bill discusses some key steps to help develop a learning mindset into an everyday habit. Watch here on YouTube, or listen via our RCVS Knowledge podcast channel.

- Critical appraisal tools can help you appraise the evidence for validity. This can be applied across all evidence presented to you. Find out more.

References

1. Hollnagel, E., Wears, R.L. and Braithwaite, J. (2015) From safety-I to safety-II: A white paper [online]. The Resilient Health Care Net: published simultaneously by the University of Southern Denmark, University of Florida, USA, and Macquarie University, Australia. Available online: https://www.england.nhs.uk/signuptosafety/wp-content/uploads/sites/16/2015/10/safety-1-safety-2-whte-papr.pdf [accessed 4 May 2023]

2. Peifer, C. et al. (2020) Well done! Effects of positive feedback on perceived self-efficacy, flow and performance in a mental arithmetic task. Frontiers in Psychology, 11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01008

3. Ellis, S. et al. (2014) Systematic reflection: Implications for learning from failures and successes. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 23 (1), pp. 67-72. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721413504106

4. Histed, M.H., Pasupathy, A. and Miller, E.K. (2009) Learning substrates in the primate prefrontal cortex and striatum: sustained activity related to successful actions. Neuron, 63 (2), pp. 244-253. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2009.06.019

5. Chiviacowsky, S. and Wulf, G. (2007) Feedback after good trials enhances learning. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport, 78 (2), pp. 40-47. https://doi.org/10.1080/02701367.2007.10599402

6. Gillespie, A. and Reader, T.W. (2021) Identifying and encouraging high-quality healthcare: an analysis of the content and aims of patient letters of compliment. BMJ Quality & Safety, 30 (6), pp. 484-492. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmjqs-2019-010077

About the author

Helen Silver-MacMahon MSc (Dist) PSCHF Cert VNECC DipAVN(surg) Cert SAN RVN

Helen is a Human Factors specialist and registered veterinary nurse with more than 20 years of experience. As part of her MSc in Patient Safety and Clinical Human Factors at the University of Edinburgh, Helen researched situational awareness in the veterinary operating theatre. She is currently undertaking a PhD exploring the human skills that veterinary nurses require when monitoring and maintaining anaesthesia and working towards chartered ergonomist status.

Helen is passionate about developing the veterinary profession's understanding of Human Factors as a powerful aid in improving patient safety, enhancing performance and supporting the wellbeing of the veterinary team. She is an RCVS Knowledge Champion for her role in the sustained training and use of a surgical safety checklist within the small animal theatre at the former Animal Health Trust. Until recently Helen was the Research and Development director of VetLed. She Is now the co-founder and Director of Being Human Consulting Ltd.

May 2023