Adopting change – Why it took 30 years to start washing our hands

This is article eighteen in an RCVS Knowledge series of features on patient safety, clinical human factors, and the principles and associated themes of Quality Improvement (QI).

Boston 1846: Anaesthesia was first demonstrated on a man who was having a tumour removed from his jaw. The pain free procedure was a big departure from the standard technique of pinning down patients while they screamed and writhed in agony. The discovery of ‘insensibility produced by inhalation’ was published by surgeon Henry Jacob Bigelow in November 1846 in the Boston Medical and Surgical Journal. The idea spread like wildfire, and by June of the following year, anaesthesia had been used in most regions of the world.

Compare this to Joseph Lister’s work on wound sepsis. In Lister’s time (1860s), infection was the single biggest killer of surgical patients. He perfected ways to use carbolic acid to clean hands and wounds and kill any germs that might enter the surgical field. Lister’s groundbreaking publication in The Lancet in 1867 demonstrated significantly lower rates of sepsis and death. You would think that Lister’s method would be adopted as quickly as anaesthesia, but the opposite is true. It would take another generation.

Both had their challenges. Lister’s method required painstaking attention to detail. Surgeons had to douse themselves in carbolic acid (which tended to burn skin), including their instruments and suture material. But anaesthesia was no easier. Obtaining ether and an inhaler was difficult, the equipment was difficult to use and it was hard to calibrate the correct dosage. But surgeons pressed on and formed a new speciality, anaesthesiology.

What are the differences? One addressed an immediate problem (pain) while the other battled an invisible problem (germs). Both made life better for patients, but only anaesthesia made life easier for surgeons. Surgeons did finally come around to Lister’s way of thinking at the end of the nineteenth century, when a group of Germans set on the idea of the surgeon as a scientist. They exchanged their blood-caked black gowns for pristine white coats and reimagined their theatres to achieve the sterility of a laboratory. 1

So, what can we learn from this? Improvement comes about when people perceive value in change, that any change that makes our lives more difficult will be slower to adopt.

When we own the change, and can imagine it for ourselves, we are more likely to adopt it as our own.

Which then begs the question, ‘Do you have a voice in improvement work?’ As people on the front line of delivering care to clients and animals, are we consulted about change, and can we make a meaningful contribution?

People are not passive recipients of change. We evaluate it, seek meaning and develop feelings toward change. Perceived value can be defined as a readiness of people to adopt change when they feel the outcome of that change will have value to them. Different types of value include:2

- Emotional - That will save lives!

- Practical - I can see myself doing this new thing

- Logical - That new process makes sense

So how do we ensure that we are adding value, not only to our patient’s lives but to the team’s lives as well? We start by supporting and engaging our team with compassion when we talk about improvement work; this investment will help us see our end goal, but how do we go about it?

Work with a shared purpose

Talk about what matters to the team and start where they feel improvements are needed. Help the team rediscover the meaning and purpose in their work by asking, ‘Why did you get into the veterinary profession?’ and ‘How do you know you are making a difference?’ This conversation needs to have a structure, so join in exploring the Framework for Improving Joy in Work, which provides some guidance.3

Working with a shared purpose taps into our intrinsic motivation, which involves doing something because it is personally fulfilling, and is generally a more effective way to help us reach goals that can take time to achieve. Extrinsic motivation involves doing something because of outside causes, such as avoiding punishment or receiving a reward. While it can be helpful in some situations, extrinsic motivation can lose effectiveness over time and could lead to burnout.4.

People doing the work are directly involved in the change

I often encounter people leading improvement projects, who have great ideas, but wonder why their teams aren’t getting on board. They ultimately ask, ‘How do I get my team to do what I want them to do?’. But this is not the right question. The questions should start with, ‘How do I engage with my team?’. ‘How do I enable them to realise their potential and work with a sense of purpose?5

Working with meaning and autonomy motivates people to take on improvement missions, where the traditional command and control style of leadership fails.

Power is the ability to act within our purpose and values. Distributing power, and moving away from top-down leadership, means that many people are working together to accomplish a shared purpose, with each person contributing their unique assets to the work. Working in this structure (where leadership is shared) the responsibility for improvement is entrusted to all team members.6

When people who do the work have the power to affect change, our mission is set up for greater success, as they know the work best.

Any intervention must be designed and piloted by those who have a role to play in implementing it. Their feedback is continuously sought and acted on, so we know if changes are having the desired effect and we can attempt to avoid any unintended consequences.6

Have courageous conversations

When setting off on any improvement mission, it is important to seek different perspectives. If we surround ourselves with ‘yes’ people, we close ourselves off to new ideas and the flow of information decreases. Inevitably, we will encounter conflicting points of view. Courage is when we choose to act in the face of a challenge, and when we strive to understand one another, the team grows stronger.5

Take time to establish how the team behaves together to achieve its shared purpose. This may include developing a working agreement, or workplace charter, to establish cultural norms, like treating each other with dignity and respect, being open and honest, and creating a safe space where people are comfortable expressing themselves. Agree together as a team on what is considered acceptable behaviour. What’s ok and what’s not ok in handling improvement work, e.g., if the team disagrees on something, how do you handle it? How will the team approach it if someone does not live up to the norms? By reinforcing positive accountability for what matters most, the team is more committed to working in a psychologically safe way. 6, 7

Work design

Now come the logistics. We are scientific and practical people who like an evidence-base and, as we learned from Joseph Lister, straightforward solutions. How we incorporate change ideas in our day-to-day work matters, if it doesn’t flow well or we don’t have what we need to implement the new idea, it will fall at the first hurdle. A few more things to consider: 8

- How complex is the change idea? Ideas that are simple, and are comprised of very few steps, are more likely to be adopted and sustained over time. A word of caution here, offering a simple solution to a complex problem is unlikely to work. Instead, break down a complex issue into small steps and address each one of these steps in turn.

- What evidence is there for this change? People will view change more positively if they perceive the validity of the evidence will lead to the desired outcome.

- Are all the resources available (equipment, training, personnel) to implement the change idea? Providing the necessary resources to implement the change and adapt to existing workflow.

- How much workload is associated with the change idea? Interventions that reduce (or don’t increase) workload or make the workflow easier to perform will be more likely to be adopted and sustained.

Sustain the work

We should spend the most time in the preparation and planning phase of an improvement mission. Taking time to engage your team in the areas as outlined above, puts you on the right foot and helps you gain momentum every step of the way, building the energy that you need to implement and carry out the work. But how do we keep the energy going to see it through? Sustaining the work isn’t going to happen by chance, so we need a strategy.

See it, every day

When testing small ideas of change, using visual tools that people see every day, like a notice board, can help the team quickly determine if they are veering away from their desired outcome. The visual system should be simple and transparent, so anyone walking by can determine normal vs abnormal in under five seconds. Once a problem is identified, the team works to identify what is getting in the way of sustaining their goal and corrects the issue.6

Improvement huddles

Improvement huddles are regular 10–15-minute meetings amongst all team members to anticipate problems or review their performance against their goals. Once the team recognises a problem, they can work to identify what is getting in the way of sustaining their goal and correct the issue.6

Celebrate!

So much of what happens over the course of a day in a veterinary practice is truly remarkable. When the team undertakes an improvement mission, celebrate every possible moment, every success and failure – as there is learning in both. Celebrate every time you have a courageous conversation and stop to acknowledge when the team is working within their purpose and values. This celebration brings us closer and keeps us energised to continue moving towards our quality goals.6

Success lies in preparation

The success of quality improvement missions lies in the preparation. We can only keep the momentum going if we have taken the time to build a strong foundation from which to work from. When people on the front line hold the power to affect change, and to imagine it for themselves, evidence is put into practice and improvement becomes reality. In Lister’s time it took 30 years to put patient safety into practice, by 2001 this was reduced to 17 years. Whatever the time lag is for the veterinary profession, quality improvement can undoubtedly speed up the process.9

Checklist: What you can do next

- Join the ‘What matters to you’ conversation with RCVS Knowledge, in the series of Vet Times articles about improving joy in work. By asking this simple question, we gain valuable insight into what lies beneath our combined commitment to give the best possible care and can be the first step to improving workplace well-being.

- Download the What matters to you – Conversation Guide for Leaders, adapted from the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) original framework, to support leaders within the veterinary sector in introducing the Joy in Work concept to their team, engaging and empowering them in continuous Quality Improvement.

- Visit our AMR Hub where you will find freely accessible, evidence-based knowledge and resources about responsible antimicrobial use. With over 42 hours of CPD, teams can access the latest resources and information to help you embed good antimicrobial stewardship and biosecurity in practice.

- Stream the free to access QI Boxset Series 1: Establishing a Quality Improvement Structure in Practice, take the course at your own pace, packed with practical information and advice from a range of veterinary professionals to help you establish a Quality Improvement Structure in Practice.

- Read the QI feature Communication – a core non-technical skill by Angela Rayner to discover the value of clear language in establishing trust and shared understanding, leading to better team collaboration, better patient care and more joy in our work.

- Listen to Shobhan Thakore from the Scottish Quality and Safety Fellowship Programme, as he gives a personal perspective on how engaging with your team can lead to greater engagement from your team, bringing them on board to deliver Quality Improvement.

- Listen to Helen Silver-MacMahon and Kelly Tillet, Knowledge Awards: QI Champions, discuss how to introduce new concepts and changes to your team in a way that will encourage uptake, and what to do if others in your team don’t share the same passion for change in Leading positive change in practice.

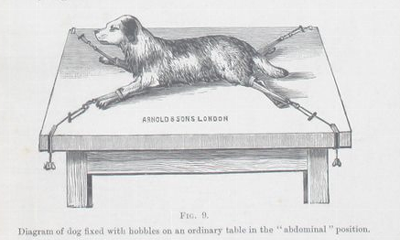

Diagram of dog fixed with hobbles on an ordinary table in the "abdominal" position.

Canine and Feline Surgery by Frederick Hobday (Edinburgh and London, 1900)

Image sourced from the Historical Collections.

References

1. Gawande, A. (2013) Slow ideas [The New Yorker. Annals of Medicine] [online]. Available from: https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2013/07/29/slow-ideas [Accessed 7 March 2022]

2. Hayes. C. and Goldmann, D. (2018) Highly adoptable improvement: A practical model and toolkit to address adoptability and sustainability of quality improvement initiatives. The Joint Commission Journal on Quality and Patient Safety, 44 (3), pp. 155-163. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcjq.2017.09.005

3. Perlo, J. et al. (2017) IHI White Papers: IHI framework for improving joy in work. [Institute for Healthcare Improvement] [online]. Available from: http://www.ihi.org/resources/Pages/IHIWhitePapers/Framework-Improving-Joy-in-Work.aspx [Accessed 9 March 2022]

4. Sennett, P. (2021) Emerging leaders: Understanding intrinsic and extrinsic motivation. [University of Rochester] [online]. Available from: https://www.rochester.edu/emerging-leaders/understanding-intrinsic-and-extrinsic-motivation/#:~:text=Intrinsic%20motivation%20involves%20performing%20a,punishment%20or%20receiving%20a%20reward [Accessed 7 March 2022]

5. Thakore, S. (2020) Getting your team on board to deliver quality improvement. [RCVS Knowledge] [podcast]. Available from: https://rcvsknowledge.podbean.com/e/getting-your-team-on-board-to-deliver-quality-improvement/ [Accessed 9 March 2022]

6. Hilton, K. and Anderson, A. (2018) IHI White Papers: IHI psychology of change framework to advance and sustain improvement. [Institute for Healthcare Improvement] [online]. Available from: http://www.ihi.org/resources/Pages/IHIWhitePapers/IHI-Psychology-of-Change-Framework.aspx [Accessed 7 March 2022]

7. Corbridge, T. (2017) How positive accountability can make employees happier at work. [Inc.] [online]. Available from: https://www.inc.com/partners-in-leadership/how-positive-accountability-can-make-employees-happier-at-work.html [Accessed 7 March 2022]

8. Hayes, C. (2015) Highly adoptable improvement model. [Highly Adoptable Improvement] [online]. Available from: https://www.highlyadoptableqi.com/tools [Accessed 7 March 2022]

9. Munro, C. and Savel, R. (2016) Narrowing the 17-year research to practice gap. American Journal of Critical Care, 25 (3), pp. 194–196. https://doi.org/10.4037/ajcc2016449

About the author

Angela Rayner BVM&S MScPSHCF MRCVS

Angela is a Quality Improvement Advisor for RCVS Knowledge, Director of Quality Improvement for CVS, and is an RCVS Knowledge Champion for her role in improving CVS’ systems for controlled drugs auditing.

In 2021, Angela completed a MSc in Patient Safety and Clinical Human Factors at the University of Edinburgh. The programme supports healthcare professionals in using evidence-based tools and techniques to improve the reliability and safety of healthcare systems.

It includes how good teamwork influences patient outcomes, key concepts around learning from adverse events and teaching safety, understanding the speciality of clinical human factors, as well as the concept of implementing, observing and measuring change, monitoring for safety, and it focusses on quality improvement research and methodologies.

April 2022